I’m breaking from the microblog format of altJD to share a longer piece I wrote for ABA’s Law Practice Magazine (July 2020). Hidden behind a paywall, I make the article in its entirety available here. – CM

I’ve often observed that my great- great-great-uncle, Elijah Hise, a lawyer who in the 1850s served as the chief justice of the (now) Kentucky Supreme Court, would likely feel quite at home in the practice of law in 2020. Other lawyers typically respond to my observation with quizzical looks and questioning. To which I note that but for a few widely adopted technology tools, the systems within which lawyers work today are all products of the Second Industrial Revolution—Uncle Elijah’s era.

While the rest of the world has evolved into the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the legal profession and justice systems in the United States most decidedly have not. In fact, in many ways, we actively work against this evolution as we cling to outmoded ways of working along with legal regulatory structures and justice systems literally breaking from strain imposed by demands of the modern world.

For many of us lawyers, the path forward into the Fourth Industrial Revolution is uncertain if not downright obscured by ambiguity—and only intensified by the increasingly rapid pace of change being wrought by technology. This has perhaps been the case for at least the past 50 years, as documented by this observation from Fenwick and West founding partner Bill Fenwick in his 1968 Vanderbilt Law Review student note, “Automation and the Law: Challenge to the Attorney”:

Computers and automation have carried organization to as high a level of efficiency as atomic energy has carried physical power. They can be expected to affect the relationship of the elements with which they work to the same degree atomic fission has affected its elements. It is submitted that most attorneys are not aware of the magnitude of changes that have taken place. Even worse, they have no basis on which to speculate about changes yet to come. Their awakening may be rude and jolting.

As a practicing lawyer for more than 20 years, I spent much of my time figuring out how to leverage technology in combination with my most human skills to supercharge my lawyering. From this lived experience, I understand the value of viewing lawyer competency broadly and holistically. And now, I spend my time in Vanderbilt Law’s Program on Law and Innovation teaching law students and practicing lawyers how to anticipate, plan for and lead through the many changes imposed by the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

This is our profession’s present challenge: Rather than experience the “rude and jolting” awakening predicted by Fenwick, how might we proactively shape what it means to be a lawyer in the 21st century? Not only do I believe we can, I assert we must. The why, what and how? The case for the Delta Model for lawyer competency.

Why the Delta Model?

Every fall in my Legal Problem Solving course, I begin with a deep dive into the many challenges we currently face in the legal profession. I do this because I believe law students—the future of our profession—deserve as much information as possible about the profession they are about to enter. This information empowers them to make informed and intentional choices as they design their professional paths. Practicing lawyers need this information, too, for the very same reasons.

Some of the myriad challenges highlighted in the ABA’s first “Profile of the Legal Profession” in 2019 include that the profession lacks diversity, remaining overwhelmingly white and male, especially at higher levels of leadership; legal professionals as a group suffer much higher rates of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, addiction, and suicide compared to the general population; and, while rates of post-JD employment have risen, the average law student debt averages a staggering $145,500, having climbed 77 percent between 2000 and 2016.

These aren’t the only challenges our profession faces. As foreshadowed by Fenwick in 1968, rapid technological advances place increasing pressure on the work done by lawyers. Traditional lawyering has commonly included drafting documents, intermediating contracts, discovering information, finding precedents, analyzing and predicting outcomes, and advising on compliance. Now, technology does all these things, and in some instances better and at lower cost, than we human lawyers. (And if not yet better, it’s simply a matter of time.) What do we do in the face of this technological redundancy?

Finally, we must acknowledge a fundamental challenge in our civil justice systems. The 2016 ABA Commission on the Future of Legal Services’ Report on the Future of Legal Services in the United States outlined these challenges. Many respondents described the current access to justice gap as an emergency, with 80 percent (or more) of people facing a legal problem doing so without help from a lawyer. And according to the 2014 Accessing Justice in the Contemporary USA: Findings From the Community Needs and Services Study by the American Bar Foundation, 85 percent of people with a civil legal problem never even enter a formal legal system for resolution.

I could digress into an entire treatise on how poorly most people fare when navigating our civil justice system. Instead, I simply assert that the data clearly establishes that the current system fails miserably those whom it exists to serve. And since lawyers are currently the sole group of people with the privilege to provide legal help, this failure is squarely on us.

What does all this mean for practicing lawyers? The best solutions to these many challenges can be found in the individuals doing the work. We make law better one lawyer at a time. Not by burying our heads in the sand and denying the changes demanded. Instead, we make law better when we seek clarity in the ambiguity and align the development of our competencies around a framework that supports our evolution into the Fourth Industrial Revolution—the Delta Model for lawyer competency.

What is the Delta Model?

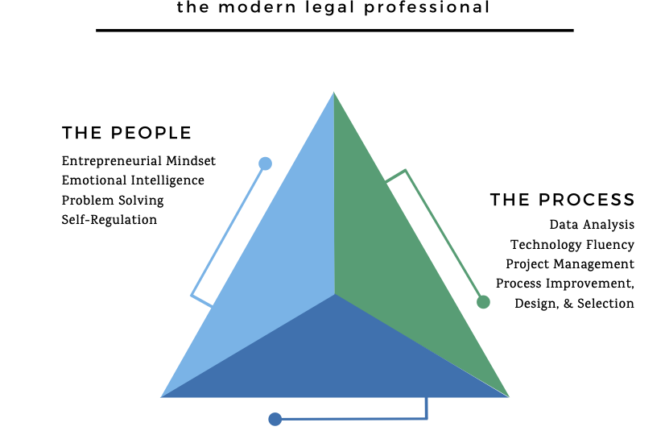

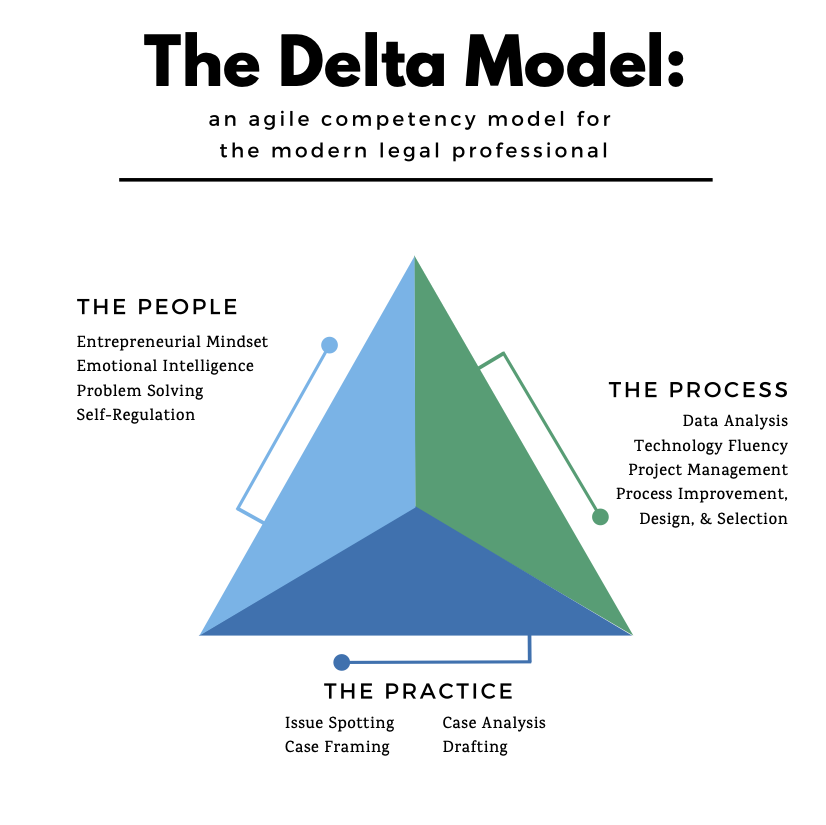

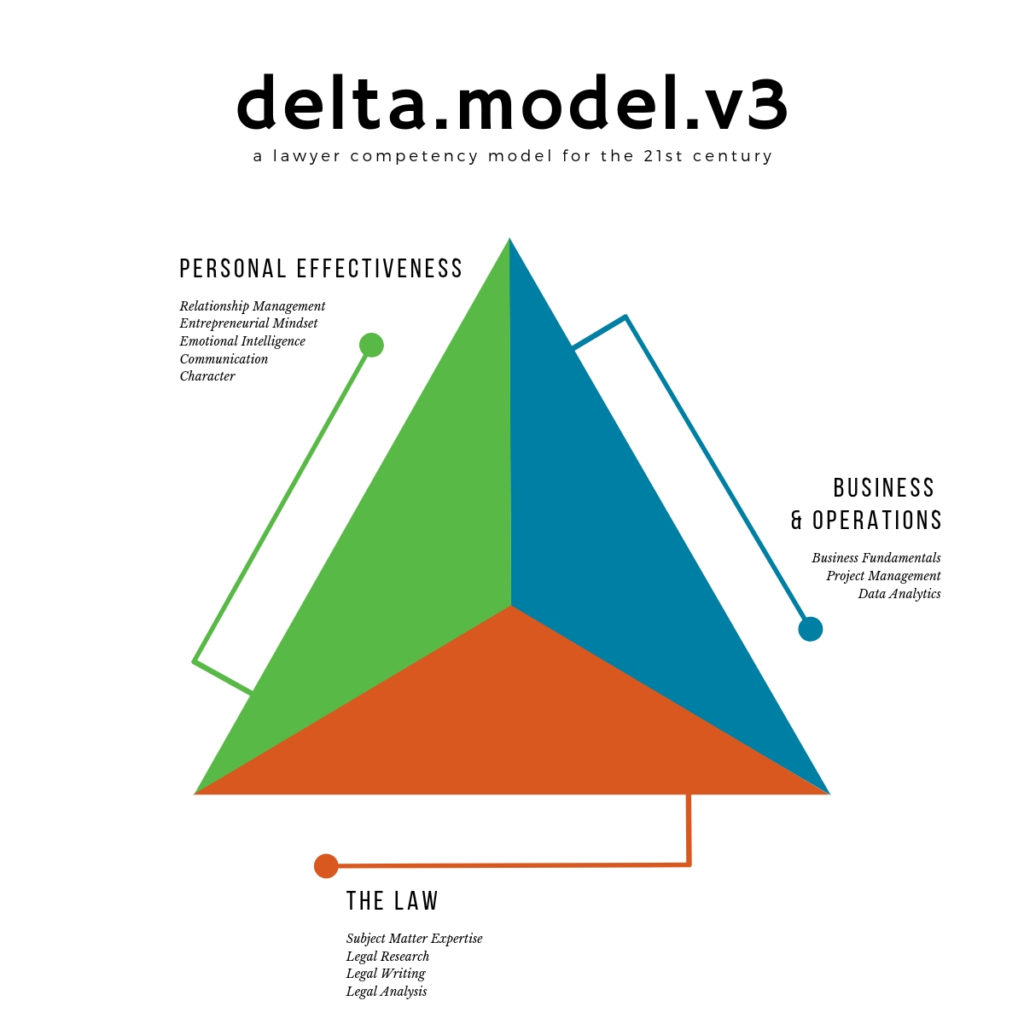

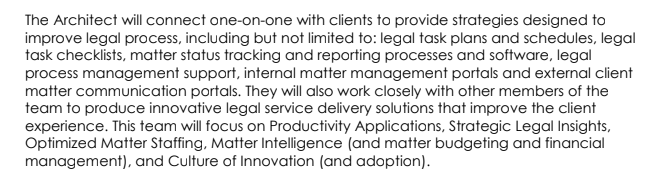

The Delta Model is a visual framework identifying and relating the core, critical skills required for legal professionals. The current iteration of the Delta Model arose from a design sprint in 2018, when working group members Alyson Carrel, Natalie Runyon, and Shellie Reid, along with Jordan Galvin and Jesse Bowman, ideated the initial model by iterating on the “T-Shaped Lawyer” concept.

A triangle with three sides, the current Delta Model encompasses the Practice, the Process, and the People competencies required to thrive as a 21st-century lawyer. The three sides in combination provide a holistic understanding of the myriad skills any given legal role is likely to require. The individual competencies included are based on both existing research and original quantitative and qualitative research performed by working group members. A white paper by Runyon and Carrel, Adapting for 21st Century Success: The Delta Lawyer Competency Model, is instructive.

The Practice dimension forms the foundation and is made up of traditional legal practice skills including issue spotting, legal analysis, issue framing, legal research, and drafting. The Process dimension forms the right side of the Delta and includes skills like data analysis, technology fluency, project management, process improvement, human-centered design, and business fundamentals. The People dimension forms the left side of the triangle and includes human skills such as an entrepreneurial mindset, emotional intelligence, problem-solving, self-regulation, communication, and collaboration.

While “thinking like a lawyer” traditionally included those competencies along the Practice base of the Delta, these skills alone will not move us from the Second into the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The research behind the Delta Model affirms that skills on the Process and People side are critical to both fulfilling our ethical obligations to those we serve and to thriving in our work. And this is further affirmed by research on the future of knowledge work that consistently emphasizes how our uniquely human skills will be key to avoiding redundancy as technology continues to expand in scope.

The name “Delta” was chosen to explicitly acknowledge that change is elemental to the framework—that we will need to adapt our competencies over time as our roles as lawyers evolve to respond to the ever-changing world in which the law operates.

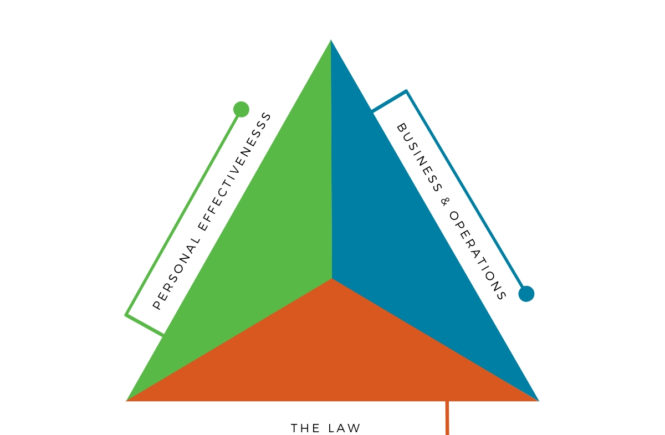

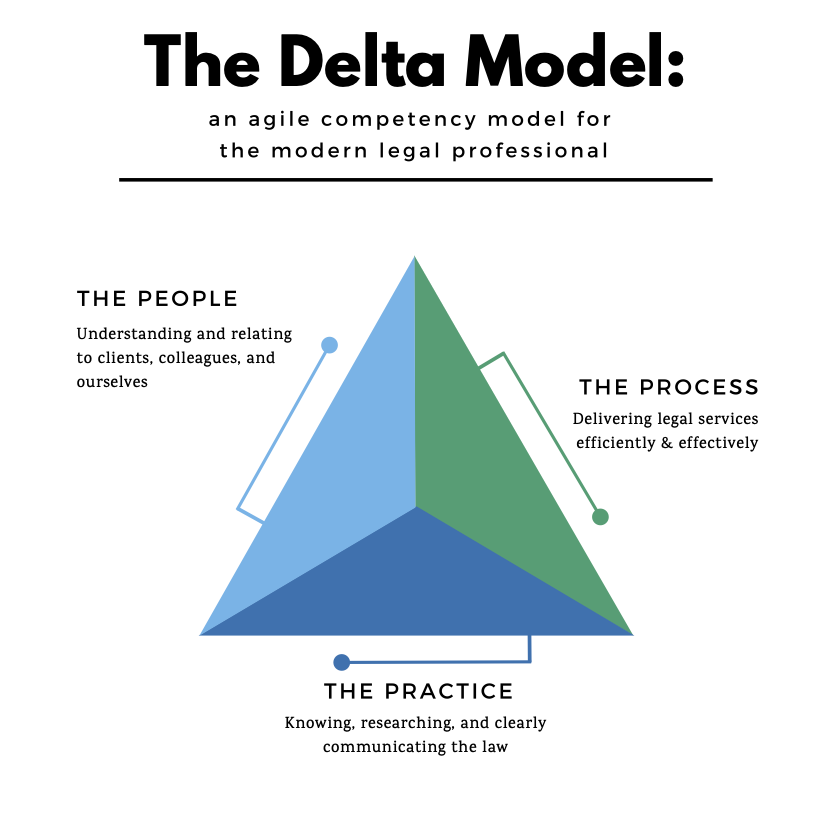

The change element also references the agile nature of the framework as it applies to any given role because there is no single model of lawyer competency that extends across roles. The equilateral Delta treats all three sides as having equal value. However, the center point of the model is designed to shift, acknowledging that certain roles require an emphasis on some skills over others. The graphic below reflects how different roles produce different Delta triangles, reflecting emphases on different competencies.

How can YOU use the Delta?

The model’s ability to reflect different combinations and levels of skills in a clear, visual way is elemental to the purpose and application of the Delta—it can be iterative for a legal professional as she progresses through her career, starting in law school.

Both Alyson Carrel and I currently use the Delta Model to help students in our courses make curricular choices in law school and set career goals intentionally. I do this in a couple of ways with students, first by having them complete a self-assessment of the competencies on a 10-point scale. Students can then overlay their Delta assessment on the Delta map for the position they seek to fill directly out of law school. This creates crucial self-awareness, as students explore both their own skills and the skills required by the role they seek to fill.

Students also complete a second assessment, this time focusing on their competencies in relation to what skills they most want to expand and focus on, regardless of where their current competency levels lie. The point of this assessment: identify any clear gaps in skills preference as compared to the skills a future position requires. This analysis opens what most of us found to be a black box when going into law absent prior experience. By explicitly revealing what the job requires, we can answer a very important question: Is this the kind of work I want to be doing?

This question is equally important for practicing lawyers, who can use the Delta Model in much the same way as students do. By explicitly identifying both (a) your current skills gaps and (b) the skills most important in your current role, you can (c) design a truly intentional and meaningful plan for professional development by focusing on your most critical gaps. Also, you can use the Delta Model to identify roles that may be better suited to your current skills and the ones you most want to cultivate.

A big reason many people leave the law? They land in a role that isn’t a good match for the skills they have and wish to grow. If, by using the Delta Model, we can help people identify and seek the best roles for them, we will keep more people meaningfully engaged in the law and make law better for all.

Finally, I want to emphasize this very personal point: Without realizing it at the time, I was a Delta Model lawyer in my practice. In hindsight, I understand that I most thrived as a lawyer when I was self-aware of my competencies as these related to my work. And I experienced the highest levels of satisfaction in my work when I exercised autonomy over choices to craft both roles and professional development opportunities in line with my own Delta.

As you venture boldly into the Fourth Industrial Revolution, I invite you to design your own Delta and create a personalized plan to identify and cultivate your skills growth. Rather than a rude and jolting awakening, you can chart an intentional course to make law better for those you serve. And for yourself.